COVID-19 booster shot hype conceals more serious problem in Hungary

Taking up first doses practically stops

The past three weeks were all about the option to get a second booster shot of a COVID-19 vaccine. The official government portal shared 3rd dose uptake data for five days straight and then it stopped on Wednesday. All we know from the last (Tuesday) report is that 52,000 of the 64,000 registered people got their third dose of a vaccine.

What’s more important, however, is that Hungarians essentially stopped getting inoculated against SARS-CoV-2.

Only about 4,000 to 5,000 people get their first dose a day, which is no wonder, given that the lack of a vaccination certificate does not create disadvantages in everyday life. Epidemiological data of the last few months are no incentive to get vaccinated, either. The 7-day average of first doses dropped to under 5,000, a number we last saw in January, at the very start of the vaccination campaign.

East-West divide in the EU

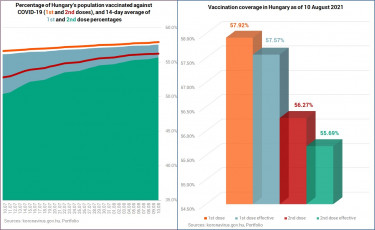

Based on international examples it seemed earlier that the vaccination rate simply cannot exceed 60 to 65% in a lot of countries. This theory has been proven wrong. Several countries now fare (much) better in this respect than Hungary which was a European champion at first.

There is an East-West divide in the EU now, with Western member states boasting higher vaccination rates than those in the East. In the region, however, Hungary’s rate is still higher than that of its peers.

Hungary is on the 17th spot in the EU ranking in terms of the percentage of the population that received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, and it’s vaccination rate is lower than the 61% EU average.

What is the response of the government then?

The cabinet is aware that the rate at which first doses are being administered has slowed down considerably and therefore launched two targeted campaigns:

- one is aimed at the elderly population (a vulnerable group),

- the other is aimed at school children (which is highly important before a new school year starts in September, kids get infected and spread the virus at home and in other communities, such as sport practices).

The government announced in early July to start a new vaccination campaign among the elderly population that had not been inoculated yet, and it did start on 1 August. In scope of this programme, GPs, voluntary physicians and medical university students personally contact elderly people that had not been vaccinated yet. GPs are already complaining about the additional administrative burdens this plan puts on them, and the thankless role of becoming door-to-door salesmen, while the government entrusted them (among others) with administering the third doses.

The impact of this targeted campaign, which has been going on for about two weeks now, is not really palpable yet:

- 76.5% of the 60-69 age group were vaccinated as of 26 July, which ratio edged up by a mere 0.4 percentage points to 76.9% by 11 August;

- in the 70-79 age group, 85.3% were vaccinated on 26 July which went up 0.3 ppt to 85.6% by 11 August;

- in the 80+ age group, the vaccination rate was 74% on 26 July which went up by only 0.2 ppt to 74.2% by 11 August.

The other campaign was targeting adolescents between 12 and 18, but they are to receive their shot in their school only a couple of days before the first semester of the new school year starts. This means, they will not have full immunity before they go into a large community where mask wearing is not going to be compulsory, either.

What could the government still do?

There are ways to further incentivise vaccinate uptake, though:

- Local physicians and a group of researchers have made a recommendation recently, saying the priority should be the inoculation of the unvaccinated population. They urged to have a better understanding of their scepticism and rejection and uncovering the regional, demographic and socioeconomic disparities in vaccination rates.

- The Mathematical Modelling and Epidemiology Task Force published a study in early August about the role of epidemiological surveillance and mathematical forecasting in preventing and mitigating pandemic waves, also presenting what has been accomplished and what should be achieved. The recommended short-term measures include the development of risk communication and crisis communication, relying on credible sources, scientific evidence and consensus. “Strengthening our epidemiological intelligence and forecasting systems, and further enhancing them in a unified framework can open up further opportunities to provide evidence-based support for decision-making processes,” they said. The researchers recommend a targeted reach of less information-savvy segments of the population (the elderly, those that do not use the Internet or who are in a disadvantaged social or financial position) to share useful epidemiological information with them (e.g. personal protective measures, the importance of vaccines, etc.).

- In various countries governments are trying to persuade the population to get their shots by implementing restrictions for the unvaccinated. (Polish government spokesman Piotr Muller has said that if the pandemic situation worsened they will need to restrict access of unvaccinated people to services and their gatherings will also need to be restricted.)

Cover photo: MTI/ János Vajda