COVID-19 in Hungary: this is why the government is bracing for the worst

Let's start with the data!

At the time this story is being written, there are 1,916 confirmed COVID-19 cases and 189 coronavirus-related deaths in Hungary. What do these numbers tell us?

- The number of confirmed cases per one million inhabitants is among the lowest in Europe (190) and the number of deceased COVID-19 patients is also extremely low.

- The mortality rate (deaths/confirmed cases), however, is really bad in regional terms, it is close to 10%, it is almost as dramatic as in the hardest-hit countries in Europe. As regards the number of deaths per one million inhabitants, only Slovenia and Romania fare worse than Hungary.

We can get an idea of the epidemiological situation in a country by looking not only at the number of confirmed cases and deaths but also at testing. As of this moment, a total fo 46,353 COVID-19 samples have been tested in Hungary. How high this figure is in global comparison?

- The nominal figure is not outstandingly low, but 4,544 tests per one million inhabitants shows one of the lowest numbers in the whole of Europe. Only Serbia, Bulgaria, Moldova, and Ukraine did worse in this respect so far.

Why testing is important

Why start with the above statements and figures? Because they are interconnected. The low number of tests explains why the mortality rate is so high in international comparison. Hungary diagnoses COVID-19 cases with extremely low efficiency. There is no mass-testing in place. Confirmed cases practically include only symptomatic patients and those that have been tested in nursing homes. In other words, authorities are willing to test for COVID-19 only when they need confirmation in suspected cases.

In light of that it should not come as a surprise that most of the diagnosed patients need to be hospitalised. They are either "caught" because they are tested in a nursing home or get accepted in the health care system only when their symptoms are already severe (or when their condition is even critical). When the country's Chief Medical Officer argues that testing will not stop the spread of coronavirus, it should not come as a shock that authorities are more than reluctant to test you just because you ask for it, even if you have very solid reasons for seeking help.

The Operational Corps started to communicate only a few days ago how many of the active cases require hospital care. As of 19 April, there were 784 such patients, which corresponds to 53% of active cases (confirmed cases minus the number of the deceased and those that recovered). At first sight, this is a staggeringly high ratio. Just recall the official statistics that claims 15-20% of symptomatic COVID-19 patients require hospitalisation.

Running so few tests have two serious consequences. Firstly, Hungarian authorities do not fathom the actual size and real process of the pandemic. Their predictive models built on the low number of confirmed cases carry serious uncertainties. Secondly, not testing enough could result in positive COVID-19 cases and their contacts not being isolated, which could make any effort to keep the outbreak in check futile.

In the meantime, the World Health Organisation and a host of other health institutions around the world cannot stress it enough how important testing is. International examples (take South Korea for instance) also show that detection is of utmost importance. The WHO stressed back on 16 March that the coronavirus must be monitored constantly, it has to be isolated and this requires relentless testing. Note that until this warning, which came two weeks after the first confirmed COVID-19 case in Hungary, Hungarian authorities took 1,470 samples altogether (150-200 tests a day), and although the daily volume is currently around the total volume then, we're still very much behind.

This is why the cabinet took that drastic measure

In times as uncertain as at present, the explanatory and predictive powers of official data are extremely weak due to the low number of tests, which makes it clearer why the cabinet has decided on the drastic move to vacate that many hospital beds, in preparation for mass infections.

What is not so easy to understand is why it is conducting this procedure so hastily while it could have been vacating hospital beds gradually.

If you cannot see the actual size of the pandemic and have a difficult time projecting the risk and timing of mass infections, a politician tries to minimise risk, i.e. starts preparing the system for a worst-case scenario. The worst cases in a politician's eye are Italy, Spain or New York where the shortage of hospital beds (and/or ventilators) doctors find themselves facing the devastating task of choosing who lives or dies. They have to treat patients in hallways or in parts of the hospital that had to be turned into COVID-19 wards in a rush.

And let's not forget the risk of an infection boom, an event no mathematical model has the power to predict. One of the potential risks in this regard is nursing homes. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has recently addressed this danger, noting that there are 1,100 nursing homes in the country (at the moment there are 20 where COVID-19 cases were diagnosed). Before that he said that even if ten nursing home residents had to be hospitalised it would mean 10,000 patients. Béla Merkely, rector of the Semmelweis Medical University and member of Orbán's team of experts, has warned that an infection boom was possible in nursing homes.

in an environment where the central strategy is to prepare for the worst, the only political answer is to submit hospital beds to the coronavirus pandemic.

Someone, though, will need to pay the piper. The price to pay will be human lives, or higher costs if you want to put it more bluntly. Why? Because patients that are "barred" from the care they need now will later return to the public health care system - if they survive that is - in a worse condition therefore their treatment could take longer, demand more serious procedures and more medication, ergo treating them will be costlier.

The Hungarian Medical Chamber (MOK) has recently sounded the alarm over the "invisible" victims of coronavirus, i.e. those that succumb to their illness because they do not get the treatment or they are not treated in time. Forcibly vacating hospital beds will only exacerbate the already dire situation.

Another "benefit" of sending people home from inpatient care is that staff taking care of these patients will now be free and can be put on alert. And with that we've reached the most vital condition of the hospitalisation of COVID-19 patients: human resources. Public health care had been long suffering from a shortage of medical staff even before the onset of the pandemic. As of mid-March, health care workers over 65 years of age are banned from making physical contact with patients, which has made labour shortage in the sector even worse. It is easy to see that the bottleneck in ICU care, e.g. treating patients requiring mechanical ventilation will be human resources rather than a lack of equipment. That is why some clinics in the country started trainings for their doctors and qualified staff on how to operate ventilators.

Government gearing up for one of the worst scenarios in the world

If our starting point is not the number of hospital beds that must be vacated but the ventilator capacity of the country, the cabinet's goals in terms of readying hospitals will seem even more drastic.

According to date obtained by Portfolio, the vacation of hospital beds would go down in two stages as follows (see a table with a county breakdown below). As you can see, there's a ministerial instruction also on ventilator capacities to be set up. This would facilitate artificial ventilation of 9,875 COVID-19 patients. (Of course, there aren't that many ventilators in the country, and some of those available help keeping alive patients that were not hospitalised because of COVID-19). This number would exceed the 8,000 PM Orbán has heralded on several occasions.

Global statistics show that about 5% of COVID-19 patients deteriorate into critical condition. So, it is easy to calculate that with an 8,000-strong ventilator capacity Hungary would "need" about 160,000 active cases, and a 9,875-strong capacity would be required if there were 197,500 active cases. Comparing these Hungarian scenarios / expectations to the current (19 April) number of active cases in Spain (99,500), Italy (107,700), France (96,500) or Germany (53,800), it becomes crystal clear that

the hungarian government is gearing up for the world's second-worst scenario in respect of the spread of covid-19.

The number of active cases is higher only in the United States at present. This begs the question: how realistic a worst-case scenario must be?

The train of thought presented above intends to demonstrate that under the government's current logic ("hope for the best but prepare for the worst") the forced rebooting of hospitals does make sense. By this, however, we do not mean to say at all that it's all right or there is no other way. Because there is indeed another way, a better way.

Global examples attest that there are alternative ways, and one of them is to do away with the starting position caused by the inadequate testing practice (with particular attention to high-risk nursing homes that should be addressed by a special action plan).

Hungary would need to put a finger on the spread of COVID-19. Authorities should gain knowledge of how the virus spreads between contacts and for that they would need to step up testing - drastically! In that case authorities would not have to prepare exclusively for doomsday scenarios (fearing we'll be the next Spain or Italy), and the principal of gradual measures could come to the fore.

What would this mean in practice? Well, the cabinet would lay down a roadmap, stipulating precisely the capacities that will need to be freed at any given point on the COVID-19 curve at specific institutions (prescribing differentiated ratios for each hospital). Mass testing obviously comes at a price. But this price would be still smaller than a spike in deaths unrelated to COVID-19 (the other scenario) and a massive deterioration of "regular" patients' health conditions.

Evidently, politicians are also beginning to realise that the ordering the flash vacating of hospital beds under the slogan "we must prepare for the worst" might not have been wise. While non-compliance initially entailed dismissals, health care officials have since then adopted a more sensible process of preparing hospitals for mass infections. The original instruction (based on a 7 April decision by the Minister of Human Resources) was to vacate 60% of hospital beds by 15 April. The institutions were given eight days (!) to comply which was practically five due to holidays (Easter). The new instruction was to vacate 50% of total bed capacity by 19 April (this translates into 32,900 beds). The next stage is 60% but no deadline was set. There is also some added flexibility. Whereas health institutions were given specific target numbers, hospitals located in the same county may "trade beds" between themselves, while respecting the objectives set for the county.

According to the latest available data, 66-67% of hospital beds were in use in Hungary. This means that out of the 66,906 hospital beds available about 22,750 (34%) were empty, i.e. patients do not have to be sent home from these. Consequently, hospitals had to vacate 10,700 beds by 19 April (50% cut). Although this is a much lower number than if all hospital beds had been "taken", let's not forget that we're not talking about numbers but people. Nearly 11,000 of them. With families. And societies are made up of and glued together by individuals, families, micro communities.

One more key aspect!

My interview subjects have given another explanation why the cabinet strives to have so many hospital beds ready to treat COVID-19 patients. In view of foreign examples (of Germany, Austria, Slovakia) and the dramatic deterioration in the Hungarian economy observed in the last month, the government might be considering lifting restrictions implemented due to the outbreak. Letting the economy out of the "quarantine" carries the risk that COVID-19 will spiral out of control (not that it is in much of a control now) and infections will skyrocket.

And we're back an the alternative solution. If local authorities ramped up testing, the economy could also be kick-started (gradually) and the cabinet should not prepare for a worst-case scenario even in health care. Germany is off to a cautious restart by setting up health care working groups per every 20,000 citizens, and one of the central elements is testing for COVID-19. Hungary has obviously chosen a different path. That is why inconsistent measures are being realised before our very eyes. Here's some food for thought. Citing experts, PM Orbán has recently projected the epidemic to peak on 3 May. He also pledged that by 3 May the country will have 5,000 ventilators (and will get another 3,000 just in case). And the cabinet insist that school-leaving exams will be held on 4 May.

Gradually lifting restrictive measures can hardly be imagined or executed without testing. Consequently, kick-starting the economy will be a risky endeavour. As long as policymakers are aware of this risk keeping a lot of (vacated) hospital beds and particularly massive ICU capacities ready is warranted.

In sum

On the whole, you're right to say the mortality rate is high; you're right to say we have to prepare for the worst and there must be enough hospital beds available; you're right to say vacating that many hospital beds will come at a high price; and you're right to say that hospital beds should be vacated gradually; and finally

you're right to say testing should be ramped up.

And it's not too late to start, either. The chart below sums up nicely how the job should be done. The average number of tests per day should be raised to the maximum facilitated by the number of tests and testing staff available (while observing other factors, such as possible reserve considerations).

**************************************

Special thanks to health care experts for their time to talk with me and their invaluable insights as well as to the authors of the following articles and interviews:

https://24.hu/belfold/2020/04/17/koronavirus-lantos-gabriella-lelegeztetogep-korhazi-agy/

https://www.valaszonline.hu/2020/04/16/koronavirus-teszt-szekely-tamas-interju/

https://www.valaszonline.hu/2020/04/14/legeza-ors-koronavirus/

http://www.atv.hu/videok/video-20200416-hogy-latja-az-orvosi-kamara-kasler-intezkedeseit

http://www.zsiday.hu/blog/28-nappal-k%C3%A9s%C5%91bb-mi-legyen-karant%C3%A9n-ut%C3%A1n

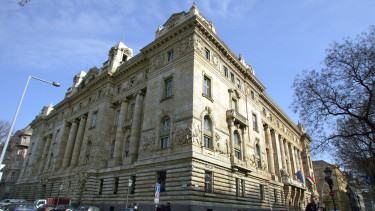

Cover photo: The Intensive Care Unit of the Bács-Kiskun County Hospital dedicated to COVID-19 patients in Kecskemét on 8 April, 2020. Source: MTI/Csaba Bús